- Home

- Beatrice Hitchman

Petite Mort Page 13

Petite Mort Read online

Page 13

At the earliest possible point, she’d look away, as if I was an embarrassment. I’d turn, go down to the automobile and ask Hubert to drive me into Paris.

Faces were just faces, seen through the car window; or they were grotesques, staring at me as if they knew me, then turning away. In the Jardin des Plantes, I walked to the leopard’s enclosure and found it asleep in the heat, half concealed by the foliage in its cage. The bookshop owner passed me the packet of new detective novels, and it seemed to me that he wouldn’t look at me, and that he withdrew his hand too quickly from the parcel.

The evenings were the worst. André seemed in a high good humour, cracking his knuckles and eating enormous portions; Luce seemed hectic, brittle, keeping up a constant stream of society chatter to which he listened, for once, with keen interest. ‘This sun will drive us all mad,’ he’d say cheerfully, when she related some idiotic, scandalous tidbit for him.

If I sometimes caught her cool gaze on me, when André was distracted by the butler, I tossed my head, miserable, and would not look at her. I’ll keep your secret, I thought, but that is all, and hated the quickening feeling in my belly, and hated even more the misery when I looked up and she had looked away.

One night, waiting for André in my room, I heard the roiling slam of thunder and the drumming of water on the leads.

I got up and crossed to the window, throwing it and the shutters wide; a gust of warm rain blew in my face. The sky was a sickened yellow; wind chased a stray newspaper across the terrace, and in the far distance, I could just make out the tree line, bending in the rising gale.

The weather seemed all the more savage in the manicured landscape: I had a satisfying vision of rose petals being strewn across the garden.

‘What a night!’ André was suddenly there, rubbing his hands idiotically as if the weather was his department. ‘Shut the window.’

‘Not yet.’ I wanted to be out in the storm, not in here with him.

‘I said close the shutters.’

‘No.’

He crossed the room and caught at my arm, pulling me away from the window, stinging my wrist; he leant out and slammed the shutters.

Immediately the room was watchful; too small and hot. He brushed his hair out of his eyes and turned away, tight-lipped, and began to unbutton his shirt, as he did every other night of the week.

I found I was trembling as I watched him. ‘You have got me here under false pretences. You have brought me here as your concubine.’

He turned to face me, smirking, fingers still unbuttoning. ‘You talk like a girl in a romance novel.’

‘You said there would be professional advancement, opportunities—’

He tried charm, striding towards me. ‘And haven’t there been chances? Peyssac, he’s famous—’

‘She barely talks to me, she won’t even look at me!’

‘Adèle—’ He took my shoulders and stroked his thumbs down them; I shrugged him off, and he grabbed me again and this time he shook me: my teeth chattered. ‘We’ve taken you in, we’ve clothed you—’

I twisted away from him, spitting out the first words that came into my head: ‘You’re wicked. You’re a wicked man.’

His lips tautened: he shook me again, harder this time.

I stared back at him, just wanting him out of my room; he looked at me, scouring my face, and then abruptly gave it up.

‘Leave, or do what you want,’ he said in disgust, dropping me back onto the bed; he crossed to pick up his shirt and stalked out of the room, slamming the door.

1. août 1913

THE NEXT MORNING I lay in bed, feeling sick.

Finally, at nearly midday, I got dressed and went to stare out of the window of my bedroom. Puddles had formed in the uneven slabs of the terrace, reflecting the blue and gold of the sky. In the far distance, a gardener nipped at the roses with secateurs.

The clock on the mantelpiece ticked the minutes into hours. Several times, I thought I heard Thomas on the stairs, only to find it was just the housemaids sweeping the terrace.

I was suddenly appallingly homesick. I sat on the bed and drew writing paper towards me; even as I dipped the pen to the creamy surface, it quivered with things to say, but as it made contact, the words faded away.

Dear Camille

Dear Camille

The pen hovered. Dear Camille.

I tore the paper into thin strips and then across again, so that only little squares were left, and those I dropped into the washstand and watched them turn into pulp.

As I turned away, my eye snagged on the carpet near the window, the spot of the struggle between André and me. There was something there.

I walked over and bent down to pick it up between forefinger and thumb. A key, finicky and lovely like everything else belonging to the house: cool and slender ceramic body, gold filigree head. It was as long as my little finger; it must have fallen out of André’s pocket last night.

I put it to my lips, tasting the metal, wondering. But then Thomas’s knock came at the door, startling me: I fumbled to hide the key in my pocket.

‘Come to M. Durand’s study in five minutes.’

André’s corridor was dark, and smelled of his pomade. A cough came from behind the door at the end, directly below Luce’s study, so that was the one I chose.

There were two tall windows but the shutters were still closed. André sat behind an enormous desk in the centre of the room, his elbows resting on its green leather top. The surface was strewn with sketches and diagrams.

Over the mantelpiece was a portrait: a woman in a flowing white dress against a green and beige background. It was too dim to see more, but I had the odd impression that she was waiting for me to speak.

André was busy writing. ‘I’m going away for a while,’ he said, without looking up. Now that my eyes were accustomed, I could see the tower of paper by his right elbow was money: tottering stacks of notes.

‘Where?’ I couldn’t take my eyes off the bills.

‘To Marseille. There’s an inventor who may have the answer to something I’ve been looking at. So I wanted to ask what you had decided.’

‘About what?’

His eyes clouded with confusion. ‘Last night, I asked you if you were staying or going.’ He looked down at his blotter again, then his hands moved independently, counting notes. ‘Because if you are going, we’ll find someone else.’

In another age, you would have said he was simple: his literal-mindedness; his ability to catalogue even things said in anger. I thought of how it had been at Pathé: how I’d loved his curly hair.

I said: ‘I’m staying.’

‘Fine.’ He threw the bigger denominations onto a separate pile. Nothing in his face to show we had ever been intimate at all.

André left the following afternoon at five. Alone in my quarters, I listened to the rap of feet in the hallway below, his cheerful shout goodbye, and some muttered conversation with Thomas – doubtless telling him to keep an eye on me. A warm summer rain fell; Hubert dashed through the puddles from the car to the front door, umbrella flaring.

You never know how much noise a person makes, how much their presence counts, until they are gone. Very soon there was absolute quiet – that absence which allows you to hear your blood in your ears. The carpets rustled in the minute air currents crossing the floor. Mice scurried about their secret business in the wainscoting.

I sat, ruminating. At last, the dinner bell rang.

I crossed to the wardrobe and opened it, and looked at the red dress hanging there.

Why not? I thought. It was mine, after all.

I climbed angrily into it, not caring if the material snagged, and then stood at the mirror and patted my cheeks red, licked spit into my eyelashes, smoothed my brow.

She turns to look at me as I come into the dining room, her mouth slightly open. I have a sudden, aching glimpse of her as a child: in the back row of a classroom, suddenly picked on by the teacher for an answer.

André’s chair is empty, his place unlaid. Thomas hovers for a moment, out of habit, just to the right of the spot where André’s shoulder would have been, then moves on to serve the first course to me.

At first everything seems as I have come to expect it. After asking me how my day was, and after my stiff response, she retreats, becoming a faintly smiling statuette; I stab at my meal.

But it is not quite normal; not quite. She says: ‘I was going to ask how you have been filling your time, since I have been so occupied with Feuillade.’ Her hand briefly touches her collarbone. ‘Was there anything worth reading in my correspondence?’

I think for a moment, then say: ‘I found a letter from one of your fans. He wishes to know why you didn’t keep to the secret rendezvous you had arranged.’

When I look up at her, she has turned pink, staring at me. ‘I know of no secret rendezvous.’

I shrug: ‘He seemed very sure.’

She stares, flushes deeper. ‘I’ve never heard of him. Truly, Adèle.’

‘He said you communicate via a private telepathy which allows you to signal to him your secret desires.’

Her eyes now clearing as she understands; a strand of her hair free and floating by her cheekbone.

‘You are teasing me,’ she says.

I smirk. ‘Admit it… the telepathy was a good touch.’

She has regained some composure; still smiling, now privately, she has swept the strand of hair back into place. ‘And what did you reply?’

‘I told him you’d meet him outside his house at midnight tonight, holding a white camellia.’

She snorts with nervous laughter, the most unladylike sound, and brings her napkin to her mouth to cover it.

The silence fills the room, making it warmer. She snaps her fingers for Thomas to open the glass doors to the garden; the evening air rolls in. She has a high red spot on each cheek.

She says suddenly: ‘I am sorry to have left you to your own devices so much recently. It was work – unavoidable. But I hope that now things are settled we may spend our days together again.’

She pauses, lips still parted as if there is more to say, then looks at me to see my response.

‘Yes,’ I say. ‘I’d like that.’

‘Good.’ She beams. The silence descends again, thick and nervous. She fusses, making a play of finishing her dessert, and we don’t speak. The red spots have expanded to her throat, which is blotchy.

At last she says: ‘Best go up,’ hitching her skirt to step free of the chair.

For a moment it seems she hesitates, as if she might say something else; then with a smile, she walks to the door.

I listen to her small, precise steps as she goes upstairs.

In bed that night, I touch myself for the first time. My hand creeps to where André used to press with his tongue, and rubs.

The sheets gather damp around my thighs. I imagine crying out to her, her laying her hands on me. Is this what my husband does? Or this?

I clamp my other hand to my mouth, in case I have made a sound.

7. août 1913

THE HEAT GATHERS ITS SKIRTS: the temperature rises hour by hour, wilting flowers, the sun huge in the sky. From Paris, the news comes of young women hurling themselves into the Seine in an attempt to cool off. They say it’s a curse, that there is a Jonah in the city – It’s the Russians, the poets, the English, the gypsies, the anarchists, the wickedness of cinema, the vengeful ghost of Josephine Bonaparte, your cousin. Your mother. Not my mother! – fights break out; the hospitals open their doors to get air: hysterics escape en masse from the Salpêtrière, whooping naked through the streets of the city.

One morning, Luce opens a note from Feuillade, reads it through and pouts. ‘His daughter is ill. They are going to Switzerland for a cure.’

She refolds it. ‘He won’t be back for months. I won’t have to spend time at the studio after all.’

She says it lightly, tossing the card back onto the pile of unopened correspondence. ‘I’ll just have to stay here and annoy you.’ She looks directly at me.

I am careful to keep my eyes on my book, but it’s too much – I have spoken, been incautious: ‘You don’t annoy me.’

Her eyes on me, cool and thoughtful. ‘What a little gentleman.’

I turn a page, hoping she won’t notice how my lip trembles.

Later, when it is too much to bear, being in the same room, I turn my head into that hanged-man posture and pretend to be asleep. Under my eyelids I watch her move to the desk and write a letter: no doubt to Feuillade, sending him condolences on his daughter’s illness. I look at every line of her, from the curve of her neck to the straightness of her fingers.

When I wake with a start, she is watching me: motionless at the desk, her pen in her hand.

‘You sleep like a child,’ she says.

The following morning, I smooth my damp palms on my skirt and go to the salon; push the door inwards, and find it empty.

I am agonised: where has she gone? Then I hear laughter through the open window, cross to it, and lean out to see her sitting in a wicker chair on the terrace below. She shades her eyes and beckons me down.

A package of books and papers has arrived – M. Leroux’s The Yellow Room and other detective novels. She fidgets, fluttering an Oriental fan; beads of perspiration trickling down her temple, reading fast, scanning the page, occasionally drawing in her breath if something surprises her, and then her eyes lift to meet mine: ‘The detective has discovered that the person who was impersonating the duchess is in fact an insane priest on the run from the mad-house,’ or ‘Apparently the murderer escaped the locked room by means of a special hatch in the ceiling, disguised as a monkey.’

Each time she laughs at the expression on my face. ‘The monkey was a good touch.’

I rarely smile back, and I never laugh. She must be able to see it all over my face.

At midday she settles her head back, folds her hands in her lap and shuts her eyes.

Searching for distraction, I pick up the Revue Satirique and flip through to the caricatures.

I stare at the page for a good ten seconds.

The caricature is a scene from a tearoom: a person sitting at a table in the foreground – a woman, by the swell of her bosom – dressed in a man’s suit and hat. She is leaning across, with her arm looped round the waist of a blushing girl sitting next to her, pulling her closer.

The woman is saying to the girl: Trousers! Practical, not just for bicycling! Underneath, there is a legend: Teatime in Montmartre: unnatural love in its natural habitat…

I look at the bow ties again, my heart thumping in my chest, the trousers the woman is wearing; at the face of the young girl shying away.

‘That’s better,’ Luce says, opening her eyes and pushing herself up in the chair a little. ‘Adèle? Are you all right?’

‘Yes.’ I put the magazine down hurriedly and try to shoo it underneath my chair.

She shades her eyes. ‘Something in the news? Something to do with home?’

‘Nothing.’ The magazine rustles against my bare feet.

She watches me for a moment longer.

Then she settles back in her chair and closes her eyes, her legs stretched out in front. Her pale skin will burn; I worry about how pink it turns, how quickly.

I practised saying it all last night, till the words sounded like nothing. She twitches, getting comfortable, and for a moment I think I almost have told her it.

But her eyes don’t snap open, outraged.

Worse: she’d be kind. I don’t understand, and then, you mean, like the ladies in the papers? But you know I am not like that. You know I’m married.

That night, I imagined what she would look like on the pillow next to me, her hair spread out like a fan. Turning to look at me: the slow blink of her eyes.

As I lay there, I heard a sound. It was like the throb of a bee against the window; I thought the insect must have got into my room during the day, so I hopp

ed out of bed and went to open the shutters, only to find there was nothing there. The panes were clear and grey in the light of an enormous moon.

Now the noise had moved, humming away down the corridor outside my room. I went to the door, opened it and listened. Definitely, the sound came from the right-hand end of the passageway – I tiptoed out and stole along, pausing halfway to listen, and laid my ear to the waxy surface of the last door. Very faint now, there was just a trilling sound somewhere beyond.

I knew all the rooms were locked, so it was no surprise when I rattled the handle and pushed to no avail. I leant my cheek on the door – I wonder – and then turned and scampered back to my room, to fetch André’s ceramic key.

It gleamed cool in the faint light; slipping it into the lock, it turned smoothly and the door swung inward.

A small bird was there, brown and indistinct except for the yellow of its eyes. A trail of broken glass led across the dusty floorboards to where it sat, shuffling and terrified; air rushed through the broken windowpane.

I went to it, cupped my hands around it and shushed it; holding it to my breast I crossed to the window and tried to push the sash up with my other hand. It was locked, the glass grimy with disuse. The bird turned its sharp beak into my skin and beat its wings; at least it meant there was nothing broken. I left the room and went to the corridor window instead, rattled it open and put the bird on the sill outside. It moved to the end of the sill without hesitation: a moment later I saw it swoop away.

Thinking of André, his punctiliousness, I went back to close and lock the door, pausing to peer inside as I did so. The room was in disuse and looked to have been for many years: there was an open fireplace in one corner, and several dust-sheeted items of furniture: a chest of drawers, a standing lamp, an old-fashioned crib. There was nothing that I could see of value; nothing remarkable enough to warrant the locking of the room or the keeping of the key about his person.

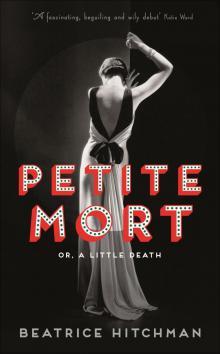

Petite Mort

Petite Mort