- Home

- Beatrice Hitchman

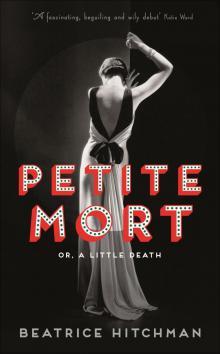

Petite Mort

Petite Mort Read online

Beatrice Hitchman was born in London in 1980. She read English and French at Edinburgh University and then took an MA in Comparative Literature. After a year living in Paris, she moved back to the UK and worked in television as a documentary video editor; she has also written and directed short films. In 2009, she completed the Bath Spa MA in Creative Writing, and won the Greene & Heaton Prize for Petite Mort, which is her first novel.

PETITE MORT

Beatrice Hitchman

A complete catalogue record for this book can be obtained

from the British Library on request

The right of Beatrice Hitchman to be identified as the author of this work has been

asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Copyright © 2013 Beatrice Hitchman

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, dead or alive, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

First published in 2013 by Serpent’s Tail,

an imprint of Profile Books Ltd

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

London EC1R 0JH

website: www.serpentstail.com

ISBN 978 1 84668 906 2 (hardback)

ISBN 978 1 84668 950 5 (trade paperback)

eISBN 978 1 84765 868 5

Designed and typeset by [email protected]

Printed by Clays, Bungay, Suffolk

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Thanks to: Antony Topping and Rebecca Gray for their brilliance, generosity and tact; to Anna-Marie Fitzgerald, Ruthie Petrie, Serpent’s Tail, Greene & Heaton; Tricia Wastvedt, Clare Wallace, Bath Spa comrades and tutors; Clare George and the SW Writers.

To Richard Abel, Ginette Vincendeau, Rebecca Feasey, Kathrina Glitre, Luke McKernan, Paul Sargent, Catherine Elliott for their help – inventions, inaccuracies or flights of fancy are mine alone. The line Who Doesn’t Come Through the Door to Get Home is an excerpt from ‘Song’ by Cynthia Zarin.

To Danny Palluel, Jo Hennessey, Churnjeet Mahn, Vin Bondah, Jen and Lucy, Tim and Ed, Pete and Lee, Anna Rutherford, Lou Trimby, Alison Coombe and LEBC, John and Lesley Hodson, the Sear-Webbs; Frank Hitchman, Bruce Ritchie, Richard and Jay Hitchman, Ellie Hitchman; my much-missed grandmother, Betty Allfree. And most of all, to Trish Hodson with love.

for T.

Le Monde, 2. juin 1967

MYSTERE!

PARIS, Tuesday – Film technicians examining a recently rediscovered silent film print, Petite Mort, have found that a segment of the film is missing.

A fifty-year-old revenant

Though it was shot in 1914, the film had never before been viewed.

An inferno at the Pathé factory destroyed the film’s source material before it could be distributed.

The film was not re-shot because of the involvement of the star, Adèle Roux, in a murder trial later that year – and Petite Mort passed into cinematic legend.

Last month, a housewife from Vincennes brought a film reel in to the Cinémathèque for assessment. She had found it during a clear-out of her basement.

The whereabouts of the missing sequence, however, remains a mystery.

Juliette BLANC

News Team

Paris

THE ASP

1909

LIGHT IN A LIGHT-BOX, light in your beloved’s eyes, is not as light as the morning sun filtering through leaves. Light in the south moves differently; everything takes its time.

Today, it moves like treacle and so do we. I and my only sister, Camille – a bright-eyed, sly duplicate of myself – are lounging on the riverbank.

For once, we’re allies. ‘We don’t have to go back,’ I say to her, trailing my fingers in the shallow water, ‘he can’t make us. She should do her work properly. We can’t do everything.’ We pause, picturing our mother straightening her back after sweeping the kitchen. Out of spite, I don’t tell Camille what I’ve come to suspect: that our mother’s ballooning knuckles make even the smallest movements painful.

‘Where will we go?’ Camille asks, turning the idea over to catch the light.

‘Oh, I don’t know,’ I answer, settling back and shutting my eyes, ‘we’ll find jobs as maids in some large house. We’ve had the practice.’

Not for the first time, I fight down the feeling that she is buttering me up: Camille should not be, at eleven, as sharp or as secretive as she is. She isn’t remotely interested in my cast-off clothes, or in dolls, or reading, or in religion; nobody seems to know what Camille is interested in. I so wanted a younger sister to admire me and to confide in, and still she simply gives the impression of biding her time.

They aren’t there, and then they are: ten boys from the village, a gang, round-shouldered and low-browed, skirting the fringes of being men. They rise in clumps from the scrub around the stream. The largest is Eluard, the stableman’s son, a boy who promises to be handsome, who knows how to charm, but whom we avoid, because everyone knows there is something wrong with Eluard. He doesn’t go to the village school any more, although the little girl lived. Her family couldn’t afford to move more than a few hundred yards up the hill away from Eluard’s family home.

‘What do you want?’ I ask, Camille standing behind me, her breath ragged. Eluard doesn’t even bother to study his nails. ‘A little kiss,’ he whispers, and makes a grab at my wrist, which slips through his grasp. The other boys step closer. Their faces look as though they’ve been melted down and clumsily pressed back together, as though someone had tried to mould them into what-is-presentable. As I step back to get away from them, the curve of a tree-trunk bumps my spine. The nearest house is a mile away.

Eluard smiles, as though it doesn’t matter that his first attempt has failed. He knows he has us cornered, and it will only please him more that there are two of us, one to be played with and one to watch the show. He stands, rocking back and forth on his heels, hands in pockets in an exaggerated display of nonchalance. As he tilts back and forth, rock, rock, I think about pushing him over and running. In my mind’s eye, I see myself streak up the hill, making a furrow in the corn, my mother opening the door to safety; I imagine Camille, left behind as the boys close in.

Eluard lays his palm under his mouth, puckers his lips and releases them. The sound hisses to us, an arrow finding its mark. ‘What if I don’t want to?’ I say, feeling Camille start to climb the tree behind us. Eluard shrugs and the boys move a step closer in, laughing at her attempts to get away. Camille’s boot scrapes a peeling off the bark by my ear. Eluard merely stands watching her, and when I can hear she is out of reach I steal a glance up. She sits atop the tree, a strange bird, black skirt buffeted by a wind that has come from nowhere. Eluard snatches at me again and this time his grip is firm, so I bite till I feel my teeth scrape bone and he yells and I jump for the lowest branch and pull myself up.

The lower branches snap as they try to swarm up the tree after me; not one of them is light enough, and each tumbles to the ground. ‘Help me up,’ I say, and Camille looks blankly at me. Then her hand wraps around mine and we sit together on the highest branch. Eluard prowls at the foot of the shelter, crying over the pointed wounds on his wrist.

‘We can wait,’ he says, and he points to the lowering sun, mouth still wrapped round his wrist. One by one they all sit down cross-legged around the tree, and all faces turn to his as he produces a stick and starts to whittle it, whistling. The sculpture is half-finished, a totem like a mandrake root, pin-head perched on voluminous bre

asts. Eluard flicks shavings off the wood swiftly and indiscriminately. Camille stares at the knife. ‘I promise nothing will happen to you,’ I say to her quietly, ‘someone will come.’ She shakes her head.

The story is an old one, and it goes like this: in the Middle Ages, our local city was under siege from the Saracens, and the people had all but starved to death. So the aldermen fattened up their one remaining animal and sent it out as a gift to the invading forces. Deducing from this gesture that the inhabitants of the city were healthy and well-stocked with food, the Saracens gave up the fight, and as they retreated, the bells of the city rang out in gratitude – carcas sona. But perched atop the sapling, ridiculous and terrified, Camille and I have nothing to offer the boys but ourselves.

After a while, the light changes, speeds up; the wind whips up clouds and a gentle rain begins to patter down. The boys grumble and kick stones, but they don’t dare to disobey their ringleader, and Camille hunches trembling into my shoulders as the rain finds a way down the back of our necks. Eluard is standing now, kicking the base of the tree savagely, his boot slipping on the wet bark. ‘When I get down,’ I whisper, ‘run for the house. It’s me they want.’ As I say this Camille studies me oddly, as though offended – how can you be so sure – but in the short silence that follows, she nods.

‘I’m coming down,’ I shout, starting to lower myself down the central branch. Away across the valley the thin wail of the evening bells begins, calling the handful of faithful, the old and the sick, to worship; Eluard smiles, just as the lanky figure of Père Simon, our priest, breaks cover from the nearby scrub and pauses, his thin legs stepping high in the long grass. ‘Adèle,’ he calls, voice full of concern, ‘whatever are you doing up that tree?’

I slither down the trunk before the world can change its mind. Camille grips my hand as we stand at the foot of the tree, while Père Simon looks at each of the boys in turn, his face blank. ‘I think this is a good enough spot for my washing,’ he says, and sits down on a rock by the edge of the river. He settles, arms folded, watching Eluard. Camille and I start up the path towards the house. When I turn, further up the hill, Père Simon is still cross-armed on the rock, and the boys are sidling off in sullen dribs and drabs.

‘He didn’t have any washing, eh, Adèle,’ Camille repeats over and over, tugging my hand all the way home.

1911

THE IRONY OF THE CARCAS SONA STORY is that church bells never meant anything to us. Around Carcassonne, we remembered another faith: cultish, medieval, heretical, and in our village, the bells were melted for scrap the year after my rescue from the treetops. We all wondered what Père Simon, who always seemed so studious and calm, could have done so wrong that he was banished by the bishops to our desolate region. Shortly afterwards, we – or rather, I – found out.

‘It’s here,’ says my eldest brother, bursting over the threshold, pigeon-chested. My father turns back to his soup, and we shift impatiently, waiting for his verdict. Eventually he nods, and we scud, Camille and I, out of the door and clatter down the hill towards the church. In the twilight, I can just make out my brothers’ silhouettes threading their way, slow and steady, down from the upper fields.

By the time we arrive, the entire village is already huddled together on the broken-down pews. At the back, I recognise Eluard and his surly, faithful followers; and at the front stands Père Simon, folding and re-folding his hands in amazement at the size of the congregation before him. The church is open to the elements, but a white sheet hangs down from the rafters, held by twin pegs and rippling in the evening breeze. Behind Eluard’s gang there is a mechanical contraption propped up on a table. A man I don’t recognise stands with one hand on a large wheel attached to the machine, watching Père Simon. A cigarette droops from one corner of his mouth, smoke trails heavenwards and, as I watch, Père Simon points at him with one trembling hand, the man begins to turn the wheel, and images begin to pour out of the white sheet.

Next to me, Camille breathes an almost silent oh. My superstitious aunt shrieks; in the front row a fully grown man kicks out his legs and snorts like a frightened horse. A woman has appeared on the sheet, sitting on a garden bench, one hand across her brow. OH! says white writing on a black background, WHO WILL RESCUE ME FROM MY PLIGHT? The woman turns to face us. She is so real, more real than anyone I know. I put my hand out in front of my face and compare it to her: she wins. Now another figure has appeared on the sheet: a man with eyebrows like upside-down Vs. He moves stealthily towards her: she cringes away from him. HELP! says the writing, I FEAR FOR MY VIRTUE! By now half the village are on their feet. The men shake their fists as the vicious baron advances, uttering words I was told I should never have to hear. And then, in a puff of smoke, grimacing wildly, the baron snaps his fingers and vanishes. The audience looks around the church, astonished. Père Simon stands up and pleads for calm; his palms try to flatten out the uproar, but Eluard is on his feet, trying to wrestle the machine out of the operator’s hands. It takes several men to drag them apart.

When the film comes back on, the woman in white is wearing a veil, standing next to a handsome moustached man. AND SO THEY WERE MARRIED says the writing. The woman turns to look at her new husband, as from one corner of the frame the vicious baron capers and grips the bars of his cage. Her look says everything: I don’t need the rest of the story to tell me how happy they will be. After the sheet goes blank, the others get up and mill about, re-enacting the story in hoarse leaps and shouts. I continue watching, desperately hoping the woman’s face will reappear.

The neighbours beg the machine-operator to tell us another story, but he snorts and shows us the damage Eluard has already inflicted on his projecting device. ‘Twelve sous,’ is all he says, holding out a calloused palm.

The following afternoon I shrug off my chores and trot down the hill to Père Simon’s house. Up close, it doesn’t seem as clean: paint peels and flutters from the door as it creaks open. And close to, Père Simon’s skin looks white and fragile, like parchment. I had always thought of him as a young man, but now I wonder how old he really is.

‘You’ve come about last night,’ he says, following me into the one main room. My mother has taught me that a lady always sits, so I take the only chair and press my knees together. Père Simon remains standing, fingers laced behind his back.

As I speak, I feel ashamed of myself and of what he must see: a girl with her hair in disarray, eyes large and pleading in a thin face. I ask him what the name of the woman is, where she lives. I ask him who was responsible for last night’s story, whether there will ever be any more like it.

He stoops and folds his hands round mine.

‘The woman’s name is Terpsichore,’ he says. ‘She has her own particular magic, Adèle, a quality all her own: one of the greats. At her first premiere, in Paris, of La Dame aux Roses, the audience was moved to tears.’

I ask him how he knows that. He pauses. ‘Because I was one of them.’

Père Simon watches me for a moment, then moves to the fireplace. He moves jerkily, just like the woman in the film, half-eager, half-held back, leading me to it: what I didn’t see before, which is that the wall above the mantel is covered, to the ceiling, in photographs of people. They are laid half over each other in a jumble, hundreds of them.

I have only ever seen one photograph before: a daguerreotype of my grandparents, who had left us the money that my father drank, and the farm we lived on. My father’s father sat; my father’s mother stood, her hand on his shoulder. Neither of them was smiling. But these: these were a thing apart – each one was a young man or a woman with a dazzling grin and gleaming hair, staring out directly at me as if it was me making them laugh.

I cross the room to look more closely.

Père Simon says softly: ‘Promotional postcards. The studios, who make the films, hand them out in advance of the films’ release.’

She is right in the centre of the display: unlike the others, she isn’t smiling, just staring bac

k at me, her huge eyes rimed with kohl, the rest of her body stretched out on a chaise longue. There is a scribble in the corner – I can just make out the words, Best wishes – and before I can stop myself I have reached out and snatched the card from the wall.

I imagine the spells I would need to transform myself into her. In my mind’s eye I see myself in a dress that shimmers like fish-scales, my face heart-shaped, all my gestures graceful, surrounded by people who love me.

Père Simon is standing with me. He sees how shocked I am, and gives a bitter little laugh and a shrug. How must it have felt for him: the young priest, stepping out from his seminary one evening, wandering the Paris streets, perhaps visiting a cinema of attractions on a whim, and leaving an hour later with his carefully constructed world a world away.

And that was how I got religion: my parents watched in amazement as I walked dutifully down the hill to visit the priest every single Wednesday. Père Simon bought a second chair, and under his careful tutelage, I studied the dramatic monologues of the great playwrights until I was word-perfect. We nursed my ambition as Cleopatra nursed the asp, letting it grow over the years.

Juliette Blanc and Adèle Roux

1967

Adèle Roux fixes me over the rim of her coffee cup: all bird bones, black sleeves flapping around the wrists. Fine silver hair in a bun at the nape of her neck and one concession to couture, a miniature hat, perched at an angle and secured with vicious-looking pins. Perhaps it’s the cup, obscuring everything below the nose; perhaps it’s the way the waiter passes behind us, whistling, or reflecting light over us with his silver tray: but suddenly I can see it. And, seeing it, can’t see how anyone can have missed it.

Watching me, she smiles. ‘You are thinking,’ she says, ‘that the cheekbones are the one thing which never changes.’

Petite Mort

Petite Mort